Ducati Triumvirate by Ian Falloon is brought to you by kind permission of Ian Falloon. During 1972 I became caught up in the Ducati 750 phenomenon. First it was Paul Smart’s victory in the Imola 200, followed by Cook Neilson and Phil Schilling’s eloquent enthusiasm in that most erudite of motorcycle magazines, Cycle. Comments like this from the October 1972 Cycle road test of a Ducati 750 GT had me captivated; “When the disc brake squeezes the bike down from three-figure speeds, when the bike connects your nerve endings to the tyre patches, when the right side peg nicks down in an 80 mph sweeper and the bike never bobbles, when the 750 leaps forward from 3,000 rpm in fourth cog-then you know. You know that a motorcyclist designed this machine and he got it right.” I wasn’t the only one enamoured. By 1975 five Cycle magazine staffers owned nine Ducati 750s between them.

Others were similarly impressed. In The Motor Cycle World magazine, Stephen DuPont claimed the Ducati 750 GT was his dream bike. He stated, “The swingarm rests near the ideal horizontal and the crankshaft lies inline and mid-way between the two axles. These two important features contribute to the 750 as the best handler I have ridden.” And then there was the engine. Unlike any other contemporary design, the 90-degree twin was barely wider than a single and offered perfect primary balance. The nearly horizontal front cylinder also allowed a lower centre of gravity. And then there was the engineering purity of the design. As on some of the most exotic pre-war racing Bugatti and Bentley cars, a complex arrangement of helically cut bevel gears and tower shafts drove the single overhead camshafts in each cylinder head. The camshafts, rolling on ball bearings, operated rocker arms without screw adjusters for dialling in valve lash. Instead, Winkler caps perched atop the valve stems had to be changed to adjust clearances. This positive cap system was more time consuming to set-up but there was no extra weight bobbing up and down on the end of the rockers, and no adjusters to come out of whack.

When Ing. Fabio Taglioni designed the all-aluminium 750cc engine he continued the familiar formula as already established with his overhead camshaft singles. The 750’s engine cases were vertically split and the 4.5 litres of oil contained in a wet sump. Thus, unlike most British bikes (and the Honda 750) there were no external hoses, clamps fittings, or outside oil tanks. And no oil leaks. As a Harley-Davidson style male and female con-rod set-up was an unfamiliar, Taglioni chose a pressed together crankshaft assembly with one-piece con-rods running side-by-side. Expensive large fibre caged ball bearings supported the crankshaft and the primary drive was by a set of helical gears to a wet multi-plate clutch. To reduce engine length Taglioni positioned the gearbox layshaft above the mainshaft. On this direct type gearbox the mainshaft was both the input and output. As a result the crankshaft rotated in the same direction as the wheels, predating modern MotoGP racing engines by decades. With dozens of carefully matched gears whirring away inside, and encased by exquisitely cast covers, the 750 engine was horrendously expensive to build. It was really a motor from an earlier era, designed and built without any concession to economics.

One might expect that Ducati, having spent a bundle on the engine, would skimp on the running gear, but this didn’t happen. Although quite heavy, the steel frame consisted mostly of straight tubes and incorporated the engine as a stressed member. This went against traditional gospel. Full cradle Duplex frames, Manx Norton style, were supposed to be the only way to get a rigid structure and proper steering. With the Ducati 750 frame this eternal tenet passed to dust. A disadvantage of the long engine was the 1530mm wheelbase, but this, combined with a very shallow 29-degree steering head angle, provided exceptional high-speed stability. The 40mm tubular steel swingarm incorporated strong Colin Seeley rear chain adjusters with a 29mm steel swingarm pivot running in generous bronze bushes. This was when many Superbikes at the time included a spindly swingarm with plastic bushes.

When it came to the suspension, wheels and brakes, the Ducati 750 GT was also at the forefront. While most Japanese and Italian Superbikes were fitted with a skinny 35mm (or even 33mm) front fork, Ducati had Marzocchi build a special 38mm leading axle fork. As it was a leading axle type the triple clamps were very flat, with minimal offset, this reducing steering inertia. The front brake was a 280mm cast-iron twin opposed piston racing style Lockheed. Again this was unique for Superbikes in 1971 and 1972. Production disc brakes at that time were mostly a cheaper single piston floating caliper type, with stainless steel discs. The stainless steel discs didn’t rust like cast-iron, but they also didn’t work that well in the wet. The Ducati’s wheel rims were also Borrani light alloy; the front with a stronger straight pull spoke design.

The result was an incredibly smooth 750cc twin that didn’t require a Nortonesque rubber biscuit engine insulating system, Kawasaki H1 and H2-like sponge-sprung handlebars, Suzuki-style fatso foot rubbers, or a tall vibration-damping top gear ratio. There was also no need for safety wire or Loctite to prevent nut-and-bolt absenteeism. And at 185kg the Ducati 750 was second only to the Norton Commando in weight for Superbikes. The styling was different, some said ungainly, but the Ducati 750 GT was a triumph of form following function.

This became evident at Imola in April 1972 when Paul Smart and Bruno Spaggiari trounced the field of works and factory-supported racers (including Giacomo Agostini on the MV Agusta 750) in the inaugural Imola 200. Their 750 Ducati desmos were simply highly modified street bikes, the frames still including centre stand mounts. This victory provided the springboard for the 750 Ducati’s success, and indeed Ducati’s success today. As Fabio Taglioni said after the race, “When we won Imola we also won the market.”

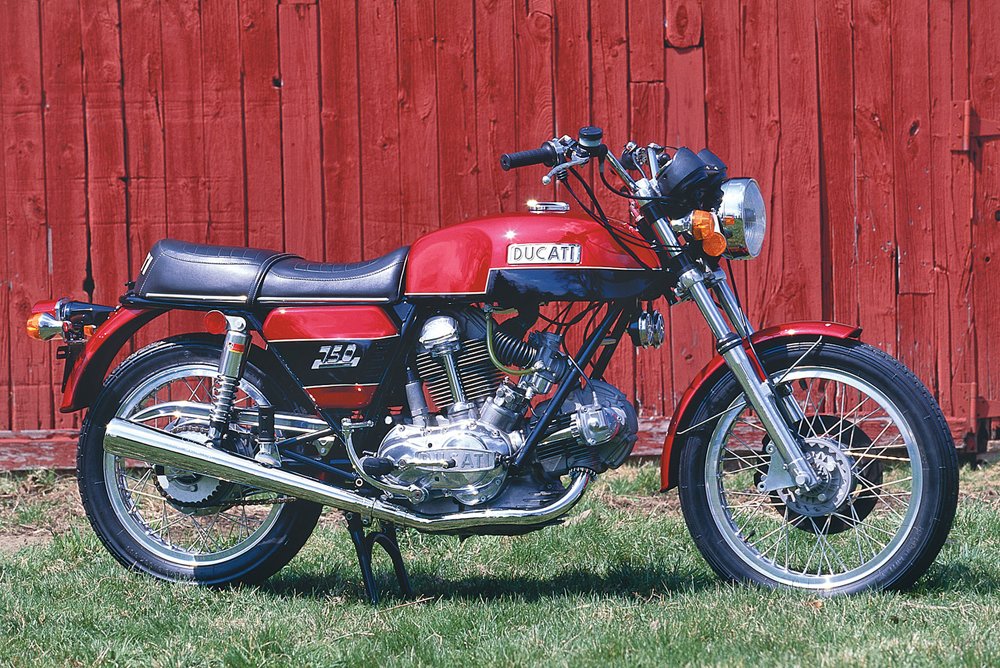

While the 750 GT’s handling was class leading, the engine performance was lacklustre. The 80mm pistons provided a low 8.5:1 compression ratio, and the engine breathed through a pair of Spanish Amal 30mm carburettors and extremely restrictive individual air filters with pleated rubber hoses. Ducati tradition demanded that a sporting version followed soon after the introduction of the GT and the 750 Sport appeared during 1972. As expected, this was a café racer with rear-set footpegs and clip-on handlebars, similar to the style of the metalflake silver Desmo singles introduced in 1971. The first Sport was based on the 750 GT, retaining the wide rear subframe but with yellow fibreglass bodywork and distinctive “Z-stripe” decals. During 1973 the 750 Sport evolved, with a narrower rear subframe and simplified decals.

It’s difficult to imagine how a pair of unfiltered Dell’Orto PHF 32mm carburettors and a couple of lighter 9.5:1 Borgo slipper pistons could transform the 750cc Ducati twin. Whereas the leisurely 750 GT ran out of breath at around 180 km/h, the 750 Sport was a different beast altogether. The headline in a November 1973 AMCN test was “At last a 130 mph 750”. AMCN actually managed 131 mph (211 km/h), the fastest 750 they had ever tested. This speed put the 750 Sport into Kawasaki 900 Z1 territory and in March 1974 Len Atlee and Tony Hatton rode a 750 Sport to victory in the Adelaide 3-Hour production race. Here they humbled the 900 Z1s of the Crawford brothers and Mick Hone/Owen Ellis. A month later Hatton was timed at 217 km/h down con-rod straight at Bathurst. The 750 Sport was a seriously fast motorcycle in 1974, and it stability was arrow like at high speed.

My first encounter with a 750 Sport was while visiting an injured motorcycle colleague at Wellington hospital in New Zealand early in 1974. I already had a 750 GT, but the image of the long, low and narrow minimalist 750 Sport parked right outside the main entrance remains embedded in my memory. This was what a sporting motorcycle should be like, and soon the 750 GT was traded on a bright yellow 750 Sport. I wasn’t disappointed. As the now defunct Revs magazine said in July 1974; “Trying to be constructively critical about this bike is hard. Everything which could be a no-no turns out to be tops.” With thunderous controllable power, tautness and response even with the horizon tilted way off level, and those Conti exhausts emitting the world’s most beautiful sound, this was my ideal motorcycle. At least until the desmodromic 750 Super Sport appeared.

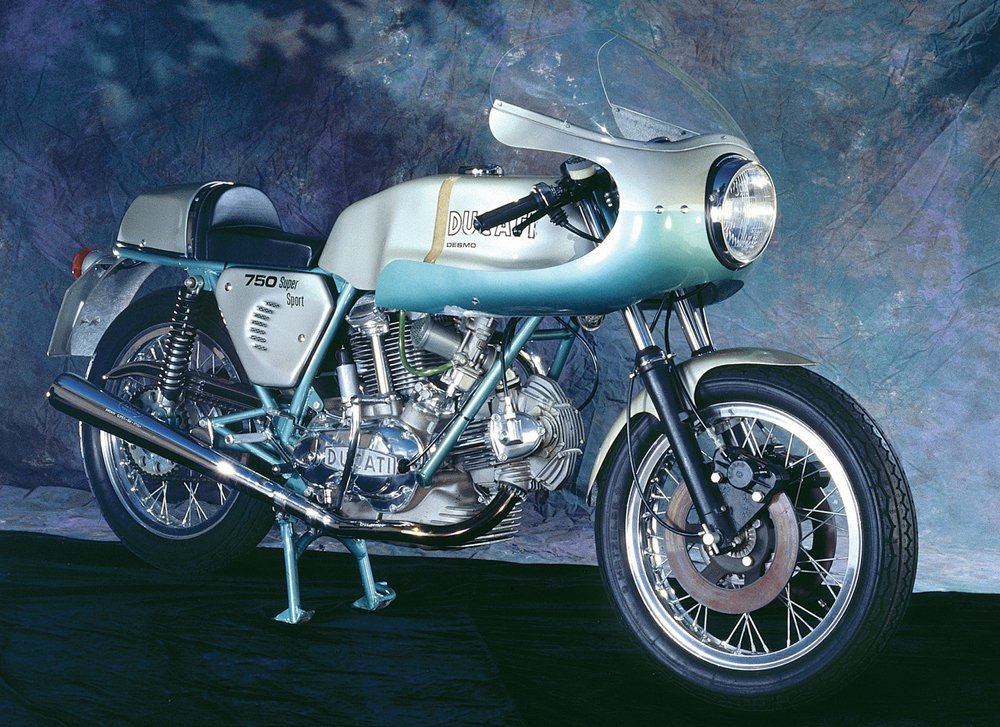

After offering tantalising prototypes during 1972 and 1973, Ducati finally released the production 750 Super Sport in early 1974; just in time to celebrate the second anniversary of Imola victory. These days it would be inconceivable to celebrate a victory that had occurred two years earlier, but the clock was slower back then. The 750 SS stretched the boundaries for production bikes. As fellow Ducati tragic Brian Cowan extolled in Two Wheels; “This lean-limbed thoroughbred is the most stunning motorcycle ever produced for the road. A triple-distilled essence of the factory production racer and an exercise in total visual harmony.” While only a few components set the Super Sport apart from the Sport, they were significant. Desmodromic valve gear, acknowledged by the almost aristocratic DESMO tank decal, came from the Imola racers. Also like the racing bikes the Super Sport breathed through a pair of huge unfiltered Dell’Orto 40mm “pumper” carbs and a clear sight strip set into the sculptured fibreglass fuel tank provided an instant fuel gauge. Completing the Super Sport’s specification was a standard half fairing, 18-inch front wheel and triple disc brakes. The Italians have a flair for investing machinery with ageless lines, and with the 750 Super Sport they excelled themselves.

Functionally the 750 Super Sport also didn’t disappoint. Although the steering was heavier, largely due to the centre axle fork flat triple clamp combination, it was more precise and the 18-inch front wheel provided more stable handling. Apart from dubious paint and finish, the main criticism levelled at the Super Sport was variable performance. The first series of desmodromic camshafts for the twin cylinder Ducatis weren’t ground with extreme precision and while some 750 Super Sports could approach 220 km/h, others were hard pressed to see off a 750 Sport. But as the 750 Super Sport was virtually unobtainable this didn’t really matter. Because there was only one batch, if you didn’t get one you missed out.

In 1974 the Ducati 750 was on a roll. Despite the oil crisis and recession, the 750 GT and Sport sold well, particularly in Australia. But the writing was on the wall. All motorcycles built after September 1974 had to shift on the left to be sold in the US. As the US market was the most important to Ducati at that time this effectively killed the round-case 750. Although 750s were sold well into 1975, production had ended before the factory closed for their summer break at the end of July 1974.

Unbeknown at the time this left the round-case 750 Ducati as a finite model. Lasting barely three years, production numbered just over 8,000 in total. Apart from a few built out of spare parts in 1978 there would be no more round-case 750s. The last time this scenario occurred was in 1955 when Vincent closed its doors. Although the Vincent twin lasted longer than three years, with around 11,000 built, there are many parallels with the round-case Ducati 750. Like the 750 Ducati, Vincent built their twin in three incarnations; Rapide, Black Shadow, and Black Lightning. The Black Shadow was produced in smaller numbers than the Rapide and offered more performance, while the Black Lightning provided the ultimate in performance and exclusivity. This was much like the Ducati 750 Sport and Super Sport compared to the 750 GT.

We are now seeing the round-case 750 Ducati replicate the Vincent twin’s appeal to collectors. Along with the Vincent Black Lightning the Ducati 750 Super Sport has become the most highly prized post war collectable motorcycle. This has dragged the lesser models along in its wake, but as with the Vincent, the gap between the higher spec versions has widened. One thing hasn’t really changed. The Ducati 750 Triumvirate is as alluring as it was between 1971 and 1974. A Ducati 750, whether a GT, Sport, or SS, did everything right back then; and continues to do so.

I would like to thank Ian Falloon for sharing this article and these wonderful pictures with us at The Motorcycle Broker. Ian Falloon has written over forty books about motorcycles, many of them about the Ducati machines through out time. He is the expert on everything Ducati and understands them with an unparalleled passion. I cannot recommend his books strongly enough, we always refer to them when we buy, they are an invaluable tool and a great read too. We will be interviewing Ian in the coming weeks, so watch out for that, it will be packed with information.

If you are interested in investing in a Ducati Round Case and want to know your classic motorcycle is investment grade, then call The Motorcycle Broker on 01803 865166 for a free, no obligation discussion.

- Most collectible Ducati 916 SP - June 20, 2024

- Classic Motorcycles: To ride or not to ride? - June 17, 2024

- Classic Motorcycles: To ride or not to ride? - June 17, 2024

The 750GT, which I own, has conventional screw/locknut tappets, not “Winkler caps”, whatever they are.

The GT was screw/locknut rocker arm operation for the valves. The Sport had bucket and shim type valves along with slipper pistons and a higher compression ration than the GT, the valve operation is correct for your GT.

I have a ’73 GT 750, It has bucket, and shim valve adjustment from the factory….. was this common?

Regards Alex

Hi Alex, the GT should have been tappet adjustment, but many people converted them to bucket and shim adjustment from the 750 Sport.

I’m afraid that’s not true. GTs had shim rocker adjustment until 1974. Screw rocker adjustment and the necessarily higher domed rocker covers became standard in the 10th and final production series in 1974.

This is true, however we have had unrestored, very low mileage and genuine examples of earlier bikes with the screw and rocker adjustment. It was a bit ad hoc.