On Tuesday I wake up to Louisa, from GS promotions banging, on my door and in her happiest, smiley voice proclaiming it’s time for breakfast. What? At 4.00am? Why? How come she’s so chipper and chirpie like a little morning sparrow, at this hour? The woman must be on medication. Everyone feels rough, we’ve had four hours sleep since Sunday morning. After a very dubious breakfast I’m standing by the coach wondering whether I’ve just eaten the meal that’s going to make me ill, and if the unthinkable does happen, how will I cope with riding the bike? There’s only one answer to this problem. Don’t even think about it. As we board the coach to take us back to the bike shop, I notice a field opposite the hotel, and an Indian kid riding a small motorcycle around the field pulling wheelies, doing jumps and generally having fun. There’s nothing peculiar about that, except that it’s 5.00am and pitch dark.

As we’d missed Monday’s scheduled ride to a town called Kumily, due to the delayed flight, the lost kilometres have to be made up today, so we’re in for a long time in the saddle. We’ve been told to ride in three groups each setting off at different times, and within the groups to ride with between two and four other people using a buddy system. This means that if there’s an accident or a breakdown, the group of two to four buddies stops and waits for the breakdown truck or ambulance, which are following up at the rear of the rally. I’m riding with an American guy, called Mike, and two English people, we’re all about the same age, late twenties early thirties. We set off and the excitement now overwhelms any tiredness, I’m here now doing what I came here to do and ready to see India. After riding for about ten minutes we leave Kottayam, the roads change, they are quieter, quite tranquil and the scenery becomes greener and more lush. I can see Mike’s bag is working its way loose from his bike so we stop. It takes a while to put it back on safely, after which we set off again. As we’ve become separated from the group riding in a pair is great fun, there’s a sense of freedom that’s not possible in a group. We can now ride at whatever pace we please, without having to worry about anyone else, and I also feel ever so slightly rebellious in not running with the pack.

Having tried to be gentle on the new machines as they’re not yet run in, we decide to see just how quickly these bikes can go, without destroying the motor, as we concentrate on catching up with the group. With a bike that needs running in, once it’s warm and the engine oil is hot, you can feel when the motor starts to get tight, so you just back off a bit. These Enfields can reach a reasonable pace even when they’re being run in. The next thirty kilometres are absolute biking bliss, long, sweeping, fast curves followed by long straights, all overhung by ancient trees with green foliage bursting with life. We ride our machines with a “James Dean” gusto; that jeans and tee shirt, with your Chesterfields stuck up your sleeve, haven’t got a care in the world attitude. It’s snowing in the UK and we’re in India in the sunshine on our Enfields having a blast.

After about forty minutes we come round a corner to see the group up ahead having stopped to fix a problem with one of the bikes. We turn up with grins from ear to ear, and it becomes apparent that our freedom is over, so we resign ourselves to returning to group riding at more sedate speeds. As we pull, there are people milling around, drinking water, talking, some are making adjustments to their bikes, others are chatting to groups of Indian people who seem to have arrived from nowhere. They’re all so polite to us, asking our names and introducing themselves in such a gentle manner. All of the men are so gentlemanly, although the women don’t talk to us, they just look from underneath their lowered brows.

After about half an hour the group sets off again and we are now embarking on our ascent into the Ghat Mountains. We’re riding through some of the most beautiful scenery I’ve ever experienced in my life, there are tea plantations to our right and a sheer drop to our left with a view of the largest horizon I’ve ever seen. India seems to have more sky than anywhere I’ve ever been in the world. We’re settling into the rhythm of the ride, and the idiosyncrasies of the Enfield, fairly well. The only imperfection to this ride, is that Mike and I want to up our pace a bit so as to enjoy the sweeping curves of these mountain roads. After our brief taste of freedom I’m straining at the leash to ride at my own pace again. We know the way, as there are no turnings off of the mountain road, so we can’t get lost and it doesn’t really seem to matter whether we’re behind or in front of the group, so we take off and go on ahead, much to the team leader’s concern.

Although the roads are appalling with potholes the size of the average grave, broken tarmac, stones and sand being just some of the hazards you’re likely to encounter when taking a corner on an Indian road, we’re having the ride of our lives. The looping curves of any mountain road are what most riders live for, and this is no exception, what is surprising though, is that it can be so enjoyable on a machine so small and agricultural as the Royal Enfield. We’re having fun in the extreme, and know that the adventure is only just beginning. Mike is ahead of me, and his bike’s exhaust note sounds like an Indian man, rapidly saying, “Mutta putta putta putta putta putta putta.”

As we progress up the mountain, our confidence is growing, so finding our selves stuck behind two buses following one another proves to be frustrating. We can see past, there’s plenty of room to pass between them and, mindful of the sheer drop on our right, Mike starts to overtake as I hang back. He starts to pass, having travelled about three or four bike lengths into his manoeuvre, the bus suddenly pulls out to pass the bus in front of it. In our cosseted world of driving with rules, mirrors and indicators, there’s no sign that this might happen, as Indian buses don’t have indicators. Mike is rapidly being pushed towards the edge and the abyss beyond, as he locks up his back wheel attempting to shed some KPH, he stands up to gain more control of the bike as the gap between that abyss and the side of the bus narrows. I’m now sure that I’m in the process of watching someone’s life about to be taken from them. Then his foot slips off the foot peg causing him to slam into the saddle and the bus misses him, by what only seems to us, an act of God. It was a close shave and time to stop and photograph the stunning scenery, as Mike composes himself, we agree that we really must slow down.

At Kumily we meet up with the group in front of us who are all as desperate for fuel as we are. I buy some sort of vegetable samosa type thing from a local restaurant and wonder if it’s going to make me feel so ill that I think I’ll die. There are about thirty of us waiting outside of the petrol station, when the owner comes along to inform us that he isn’t opening, as it’s a religious holiday. We push onto the next town, which looks a little bit like the Glastonbury festival on a sunny day, inhabited by Indians and Enfields. There we not only get petrol, but also severely harassed by children wanting money.

The next part of the ride is fairly fast, long straight roads, which dip up and down. Then more picturesque, coiling, mountain roads where we get lost and ask the way thinking that we’re on a dirt track, only to find out that it’s the road to our destination, which meanders across the mountains. We cross the border from Kerala into Tamil Nadu without even stopping. It’s immediately obvious from the moment you cross the border, how much poorer Tamil Nadu is, the appalling roads deteriorate even more, the buildings are predominantly wattle and daub, rather than brick and cement. Even the adverts are for more basic things such as Pepsi and Fanta instead of mobile phones and flush toilets.

We have to rush the last hour of the ride, as we’re anxious not to have to ride in the dark in the mountains. As we come round a corner on the mountain some riders flag us down, it appears that an Indian on an Enfield has crashed into one of the girls, as he came round a corner on the wrong side of the road. Both are all right, but a bit shaken in spite of their bikes being written-off.

We continue on through the mountains, as the sun starts to play its final game of peekaboo for today. I want to go faster, but feel scared of a vehicle coming round a corner at me on the wrong side of the road. I know; I’ll use the horn. As I approach the corner I hoot the horn, if there’s something coming it’ll hoot back! Hey! I’ve discovered horn language, it works, I can ride much safer and much faster. Now I understand why Indian drivers are always hooting their horns, it’s a language, like a bat uses high-pitched squeals as sonar. You hoot your horn, if nothing comes back then it’s clear, if it isn’t clear then someone will answer your call…most of the time. It’s a non-aggressive, yet assertive way of claiming your space on the road, it can mean I’m here, I’m coming, get out of the way, don’t even think about it or even oh, ok then.

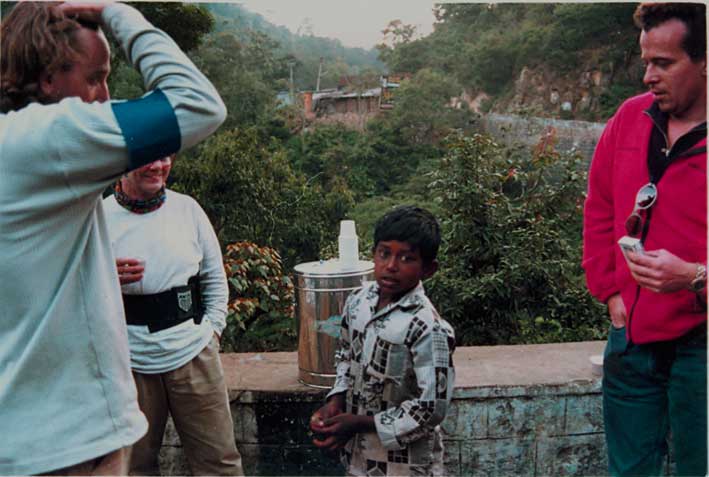

We stop about two kilometres from the hotel to drink chai being sold by a young boy of about eight. This child is so efficient and direct, with dynamism rarely seen any where in the world; as I approach, he looks me in the eyes and says, “You, you want chai?”

Of course I want chai, why wouldn’t I want chai, chai is perfect for this moment right now. So I answer a simple, “Yes”. The boy arranges the order of serving us in his own way and all of us have a deliciously refreshing, hot chai. This child knows what he wants and how to survive at the age of eight. This chai was the best ever chai I have ever tasted in my like- ever!

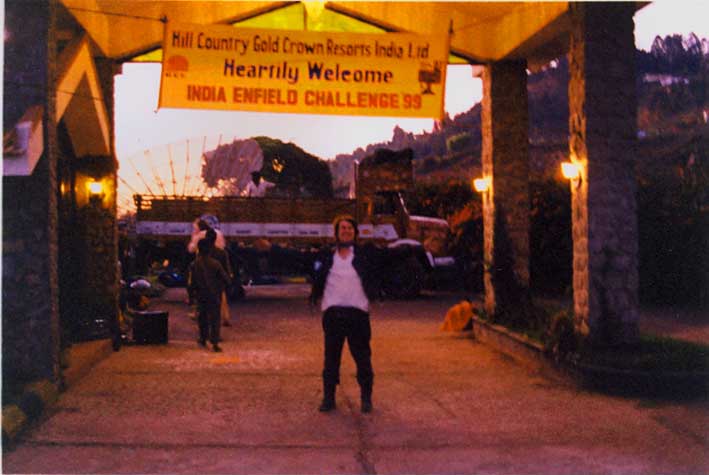

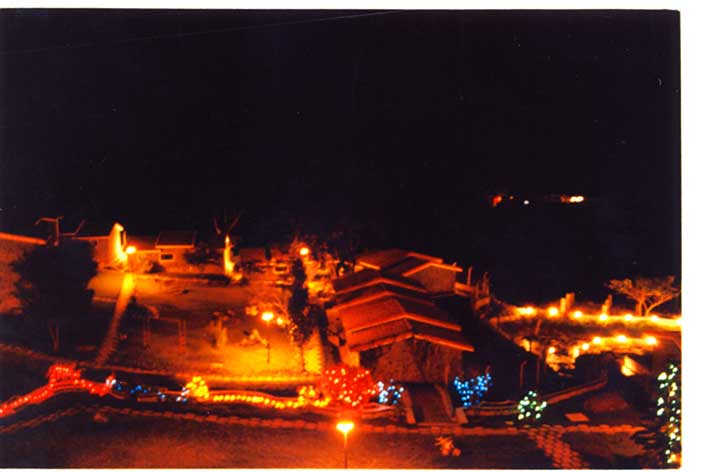

We arrive at our destination, Kodai Kanal, as the sun is beginning to set. The hotel is stunning, a five star palace which is quite a surprise, I for one was expecting to rough it.

Yet again we’re treated like royalty. Everywhere we go we feel like heroes when we arrive. This type of kindness seems to be a normal part of Indian culture. Dinner is a banquet followed by a fire outside, a dance by an Indian man who balances a particularly unwieldy head-dress on his head. He then climbs feet first backwards up a ladder, which is leant against a wall, then he comes down again and stands facing us with the fire roaring behind him. He places a needle in the tear duct of his eye, balances on one foot, moves around in a circle to show his audience that the needle is truly lodged in his tear duct. All of this whilst still balancing the cumbersome head-dress on his head. Then there is an Indian break-dancer, who’s so good he looks like he wouldn’t be out of place dancing in the ghettos of Harlem. Then we’re treated to a dancing snake charmer, who puts a very angry looking cobra in his mouth, and two other furious looking snakes down his trousers. Being outside by the fire adds so much to the spectacle and mysticism. I’m so shattered that I’m in bed by midnight, in spite of wanting to sit up talking about the days ride, as it’s certainly been one of the best I’ve ever had.

- Most collectible Ducati 916 SP - June 20, 2024

- Classic Motorcycles: To ride or not to ride? - June 17, 2024

- Classic Motorcycles: To ride or not to ride? - June 17, 2024